In light of the CIA Torture Report said to be declassified today, Asim Qureshi, Research Director of CAGE examines the use of the iconic orange jumpsuits from the detainees in Guantanamo and Abu Ghraib to the hostages kept by the Islamic State. Islamic State's tactics have been taken directly from the American government in their use of torture techniques such as waterboarding and mock executions - evidencing that the War on Terror and the impact of these torture policies affect mostly those who the they claimed they sought to protect. In 2003, I completed my Masters dissertation on the treatment of detainees at Guantanamo Bay with the following words: "If these soldiers are not afforded any of the protections that the Geneva Conventions seek to provide, then they would be not be bound to apply any of the other humanitarian standards relating to the conduct of hostilities. What would be seen, is a backsliding of conduct where warfare would become increasingly brutal. It would thus make sense for the superpower States to reconsider the rules relating to armed conflicts, as if they do not, they will find their own soldiers in increasingly difficult situations, as those they face may not care to give them any form of protection. The 'unlawful combatant' must be deleted from legal speech, and instead a positive move should be made to understand the real nature of war to accommodate for its changing nature and complexities. This may require the powerful States to look past their own emphasis on sovereignty, and take into account real humanitarian issues. The result would be of the greatest benefit to those who are caught up in the politics of States, the combatants." My first encounter with the impact that Guantanamo would have on the world, came through my investigation work in the Horn of Africa in 2007. Speaking to the chairman of the Hagdera Refugee Camp in Dadaab, Kenya, I was told that their seventeen year internment was like they had been detained in Guantanamo Bay. Only five years into the detention life of the GTMO detainees, its international symbol as a reference point for arbitrary detention was only too stark. As my investigations in Africa took me further into the complex network of unlawful detentions and renditions, a group of foreign nationals who had been placed on rendition flights from Kenya, through Somalia and on to Ethiopia were brought before a Ethiopian court. There, they were told that the Kenyan authorities were trying to determine whether they should be tried as 'unlawful enemy combatants' - the very legal anomaly my dissertation sought to expose. These detainees were housed in chicken wire cages, reminiscent of the cages that had been used at Camp X-Ray. The pseudo-legal rhetoric of the US was now finding its way, like a malignant cancer, into the heart of detention policy around the world. Although my concern had largely been in relation to the way in which states upheld the Geneva Conventions, wider international humanitarian law and more generally the laws of armed conflict, a dangerous precedent had emerged. The imagery of detainees, on their knees, with black hoods and orange jump suits in Guantanamo and Abu Ghraib, had once again found its way into public consciousness, with the public display of the US journalist James Foley and British aid worker Alan Henning by the Islamic State. In videos released by the group, they displayed Foley and Henning in full Guantanamo orange, a message to the world that the policies of the past, were now being revisited, except this time by those who had been previously subjected to the same colour in the US detention sites of Iraq. I had witnessed the same use of Guantanamo orange before, with detentions of detainees in Iraq during the years of the conflict. This time, however, there seemed to be something much more real about the way these men mirrored the sense of hopelessness of those who continued to be detained in Cuba. What really struck me though, was the reports of one technique in particular - a technique that finds its historical roots in the torture of Muslims during the Spanish Inquisition under the reign of Ferdinand and Isabella - water boarding. In the article written by Rukmini Callimachi in the New York Times, the symbolism of Guantanamo Bay and water boarding featured heavily in treatment of western hostages under the authority of the Islamic State: "In a video, they lined up the French hostages in their brightly colored uniforms, mimicking those worn by prisoners at the United States’ facility in Guantánamo Bay, Cuba. They also began waterboarding a select few, just as C.I.A. interrogators had treated Muslim prisoners at so-called black sites during the George W. Bush administration, former hostages and witnesses said." The 183 mock executions that had been carried out against Khalid Shaikh Muhammad in unknown black sites around the world, were now being visited on the hostages under Islamic State custody. The architects of the US torture programme were not the ones to suffer; it was those who were left open to the legacy of the torture, abuse and suffering that those policymakers had left in their wake. It is not George W Bush or Donald Rumsfeld who have been placed through a series of mock executions; it is the very people they said they were protecting when subverting the US constitution to carry out the most extreme forms of torture. The Islamic State exists, and it has not only secondary experience, but lived experience of the abuses carried out in the name of the War on Terror. The danger of that lived experience is not in just its disenfranchisement of those affected, it is that it will be given further oxygen to the idea the other new forms of abuse will somehow bring this conflict to an end. Ultimately, as I concluded in my dissertation, it is never those in positions of authority who suffer at the sharp end of this abuse; it is those who need to be protected.

<em>In light of the CIA Torture Report said to be declassified today, <strong>Asim Qureshi</strong>, Research Director of CAGE examines the use of the iconic orange jumpsuits from the detainees in Guantanamo and Abu Ghraib to the hostages kept by the Islamic State.

Islamic State's tactics have been taken directly from the American government in their use of torture techniques such as waterboarding and mock executions - evidencing that the War on Terror and the impact of these torture policies affect mostly those who the they claimed they sought to protect. </em>

<span style="font-weight: 400;">In 2003, I completed my Masters dissertation on the treatment of detainees at Guantanamo Bay with the following words:</span>

<em><span style="font-weight: 400;">"If these soldiers are not afforded any of the protections that the Geneva Conventions seek to provide, then they would be not be bound to apply any of the other humanitarian standards relating to the conduct of hostilities. What would be seen, is a backsliding of conduct where warfare would become increasingly brutal. It would thus make sense for the superpower States to reconsider the rules relating to armed conflicts, as if they do not, they will find their own soldiers in increasingly difficult situations, as those they face may not care to give them any form of protection.

The 'unlawful combatant' must be deleted from legal speech, and instead a positive move should be made to understand the real nature of war to accommodate for its changing nature and complexities. This may require the powerful States to look past their own emphasis on sovereignty, and take into account real humanitarian issues.

The result would be of the greatest benefit to those who are caught up in the politics of States, the combatants."</span></em>

<span style="font-weight: 400;">My first encounter with the impact that Guantanamo would have on the world, came through my investigation work in the Horn of Africa in 2007. Speaking to the chairman of the Hagdera Refugee Camp in Dadaab, Kenya, I was told that their seventeen year internment was like they had been detained in Guantanamo Bay. Only five years into the detention life of the GTMO detainees, its international symbol as a reference point for arbitrary detention was only too stark. </span>

<span style="font-weight: 400;">As my investigations in Africa took me further into the complex network of unlawful detentions and renditions, a group of foreign nationals who had been placed on rendition flights from Kenya, through Somalia and on to Ethiopia were brought before a Ethiopian court. There, they were told that the Kenyan authorities were trying to determine whether they should be tried as 'unlawful enemy combatants' - the very legal anomaly my dissertation sought to expose. These detainees were housed in chicken wire cages, reminiscent of the cages that had been used at Camp X-Ray. The pseudo-legal rhetoric of the US was now finding its way, like a malignant cancer, into the heart of detention policy around the world. </span>

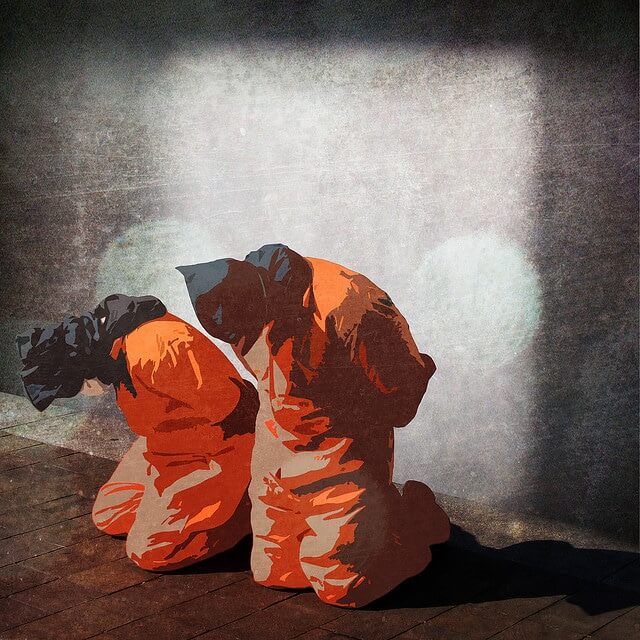

<span style="font-weight: 400;">Although my concern had largely been in relation to the way in which states upheld the Geneva Conventions, wider international humanitarian law and more generally the laws of armed conflict, a dangerous precedent had emerged. The imagery of detainees, on their knees, with black hoods and orange jump suits in Guantanamo and Abu Ghraib, had once again found its way into public consciousness, with the public display of the US journalist James Foley and British aid worker Alan Henning by the Islamic State. In videos released by the group, they displayed Foley and Henning in full Guantanamo orange, a message to the world that the policies of the past, were now being revisited, except this time by those who had been previously subjected to the same colour in the US detention sites of Iraq. </span>

<span style="font-weight: 400;">I had witnessed the same use of Guantanamo orange before, with detentions of detainees in Iraq during the years of the conflict. This time, however, there seemed to be something much more real about the way these men mirrored the sense of hopelessness of those who continued to be detained in Cuba. What really struck me though, was the reports of one technique in particular - a technique that finds its historical roots in the torture of Muslims during the Spanish Inquisition under the reign of Ferdinand and Isabella - water boarding. </span>

<span style="font-weight: 400;">In the article written by Rukmini Callimachi in the New York Times, the symbolism of Guantanamo Bay and water boarding featured heavily in treatment of western hostages under the authority of the Islamic State:</span>

<span style="font-weight: 400;">"In a video, they lined up the French hostages in their brightly colored uniforms, mimicking those worn by prisoners at the United States’ facility in Guantánamo Bay, Cuba.</span>

<span style="font-weight: 400;">They also began waterboarding a select few, just as C.I.A. interrogators had treated Muslim prisoners at so-called black sites during the George W. Bush administration, former hostages and witnesses said."</span>

<span style="font-weight: 400;">The 183 mock executions that had been carried out against Khalid Shaikh Muhammad in unknown black sites around the world, were now being visited on the hostages under Islamic State custody. The architects of the US torture programme were not the ones to suffer; it was those who were left open to the legacy of the torture, abuse and suffering that those policymakers had left in their wake. It is not George W Bush or Donald Rumsfeld who have been placed through a series of mock executions; it is the very people they said they were protecting when subverting the US constitution to carry out the most extreme forms of torture. </span>

<span style="font-weight: 400;">The Islamic State exists, and it has not only secondary experience, but lived experience of the abuses carried out in the name of the War on Terror. The danger of that lived experience is not in just its disenfranchisement of those affected, it is that it will be given further oxygen to the idea the other new forms of abuse will somehow bring this conflict to an end. Ultimately, as I concluded in my dissertation, it is never those in positions of authority who suffer at the sharp end of this abuse; it is those who need to be protected. </span>